Guider's family later moved to Sydney. His childhood was dysfunctional and he and his younger brother Tim spent time in institutions. Both were sexually abused by a man known as Mr Goddard (now deceased).

In his adulthood, while living in Sydney, Guider became a systematic and skillful abuser of children, mostly girls. He would, for example, babysit children for someone, and give them Coca Cola laced with the sleeping tablet Normasin. He would then abuse and photograph them while they were asleep. He kept extensive albums of photos of these children in various states of undress. He also kept albums on missing children.

The law finally caught up with Guider in 1996 when a mother went to police after her daughter had been abused by Guider. He was sentenced to a minimum of ten years imprisonment for sixty offences of child abuse.

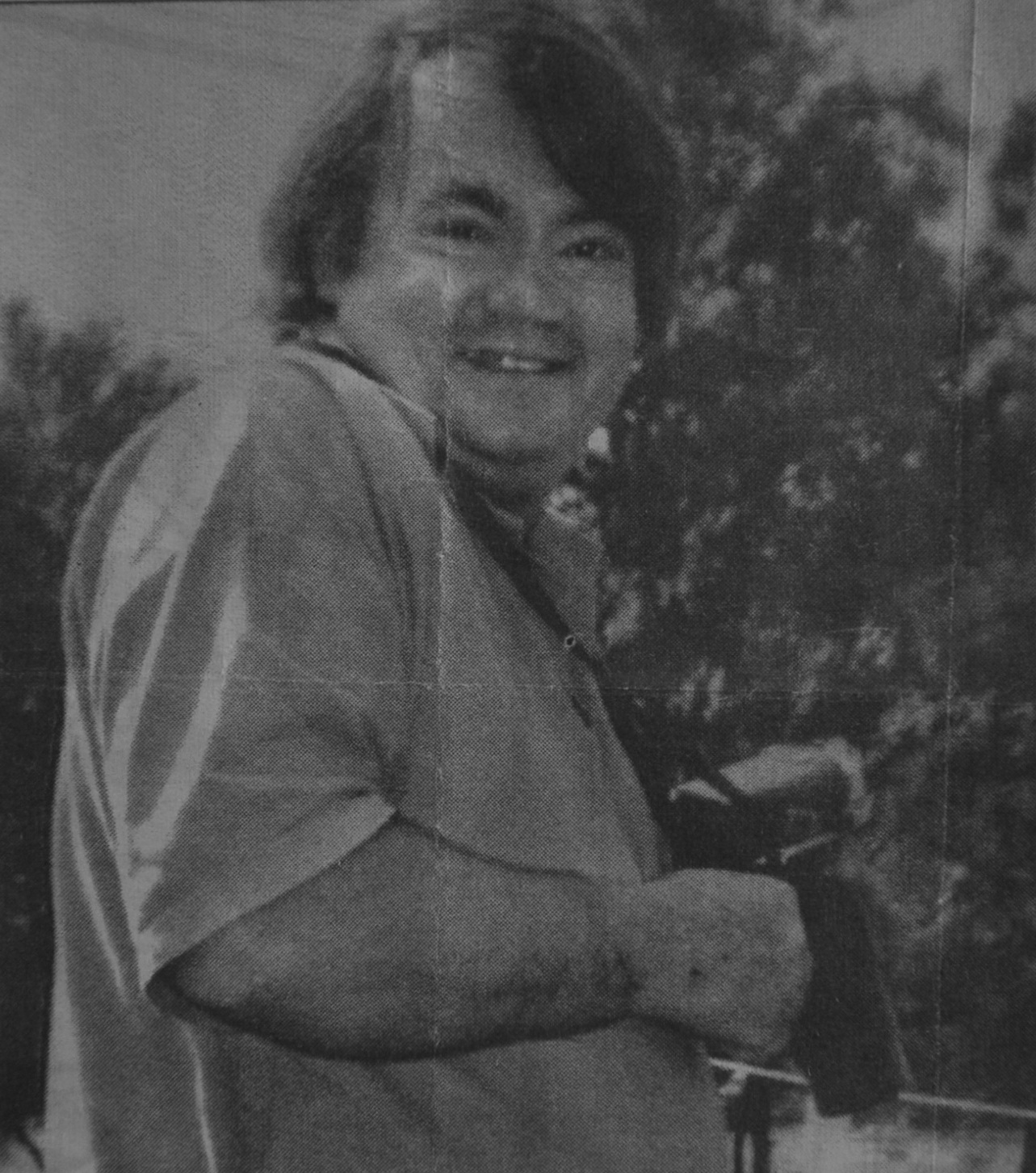

SAMANTHA KNIGHT

Freelance journalist Di Michel, who knew Guider in connection with Aboriginal sites around Sydney (he had some recognition as an amateur expert on this subject), began to suspect that Guider had some kind of connection with Samantha Knight, a nine-year old girl who had disappeared from her Bondi home in 1986, because he was always talking about her. Michel did not want to go to the police with this information, but communicated her suspicions to Denise Hofman, who had also been working with Guider in connection with Aboriginal sites. Hofman then communicated these suspicions to the police, who were eventually able to connect Samantha's disappearance with Guider. In 2002, he was charged with her murder, but pleaded guilty to manslaughter. He maintained that he had drugged Samantha with Normasin in the same way he had drugged his other victims, but had accidentally given her an overdose. He was sentenced to a maximum of seventeen years imprisonment, with a minimum of twelve, but it was made concurrent with his other sentences, with the result that it only added eight years to his sentence. In effect, he got eight years for killing a child.

Samantha's body has never been found. Guider gave conflicting versions of what he did with her, at first saying he could not remember. Later, he said he had buried her in Cooper Park, in the suburb of Bellevue Hill, but dug her up later and put her remains in a dumpster at the Royal Sydney Yacht Squadron, in the suburb of Kirribilli, where he worked at the time as a gardener. In 2003 he told police he had buried Samantha in the garden at the Yacht Squadron. In May 2003, a dig was carried out, with cadaver dogs sniffing at every soil sample. Eventually, the dogs showed a positive reaction to the soil. Their handlers said it was as positive as the dogs were capable of being. In spite of this, no body was found at the site.

WHAT HE DID WITH THE BODY - POSSIBLE SCENARIOS

The question of how Guider disposed of Samantha's remains has caused a great deal of debate over the years. Most of the scenarios that have been put forward, including the idea that she was buried somewhere in the bush, have been based entirely on speculation. If we put speculation aside, there are only two definite facts that we have:

Fact One: The sniffer dogs reacted positively to the soil at the Royal Sydney Yacht Squadron.

Fact Two: No body was found.

These two facts together imply that Samantha was buried at the Yacht Squadron, but someone dug her remains up later and moved her.

Who dug her up? It had to be either Guider or the builders who excavated the site later in the process of building an underground car park. We can rule the builders out because this scenario means that Guider -- who knew the site was going to be excavated to make way for a car park -- would have left the body there knowing very well the builders would dig it up. How likely is this? Not very likely at all. Therefore, in all probability, it had to be Guider who dug Samantha's remains up.

The next question is, naturally, how he disposed of the body. It is possible that he was telling the truth when he later told prison inmates that he put Samantha's remains in a dumpster or something similar. This means, of course, that her remains would have gone to a landfill somewhere and could never be found. This scenario can never be tested because it is impossible to know which landfill the body might have gone to. Even if we did know, it would be impossible to find a body more than thirty years after the event.

This still leaves the question of why Guider told the police Samantha was buried at the Yacht Squadron when he knew her body was no longer there. There are two possible explanations that spring to mind. One is that he was playing games with them for the fun of it, deriving a sense of power from being able to keep them dangling. The other is that he thought he might get some brownie points by putting on the appearance of cooperating with the police. In other words, if he had any hopes of getting out of prison when he next came up for parole, it would be in his favour that he had cooperated with the police by telling them where the body was. If he was challenged on the fact that the body was not there, he could always say the builders must have removed it without noticing when they were working on the car park.

There are two other scenarios that should be mentioned. First, some detectives believed that Guider buried Samantha at the Yacht Squadron and planted a tree over her so she could not be dug up. This scenario could be tested simply by getting an arbourist to see if there are any trees that could have been planted in 1986. If there is, the tree would have to be torn up. Speaking personally, I would be happy to pay for the arbourist, just for the sake of clearing things up, but it would require the permission of the Yacht Squadron, who would probably not be interested.

Second, Guider's brother Tim has a theory that Guider dug Samantha up in 1988 and buried her in a grave at Gore Hill Cemetery, in the suburb of St Leonards; specifically, the grave of Sarah Knight, who died in 1916. This could be tested by doing a scan, but this would not be easy to organise, especially on the basis of nothing more than a theory. Anyone who wants to read more about this should go to Tim's website, findsamantha.com. Tim has also published a book, Good Brother Bad Brother, which covers these matters in more detail.

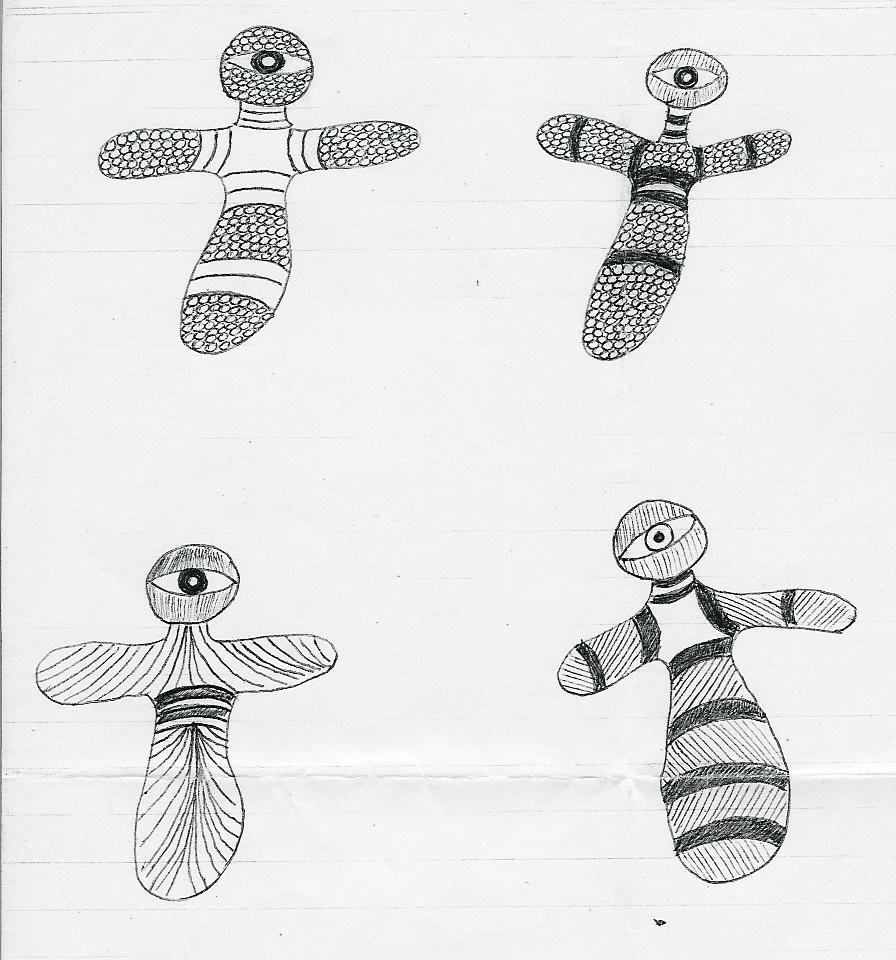

There is another interesting detail that should be covered. When he was in prison, Guider did a drawing which he gave to Tim. The drawing depicts four doll-like figures with no hands or feet, and just one eye in the middle of the face. Tim interpreted this drawing as a coded way of depicting the gravesite where Guider buried Samantha, specifically the grave of Sarah Knight. Having seen the gravesite, I can see no resemblance between the site and the drawing. If I can permit myself a personal opinion, I have my own ideas about what the drawing really represents: four victims. In other words, Samantha was not Guider's only victim. There were four, which would make Guider a serial killer.

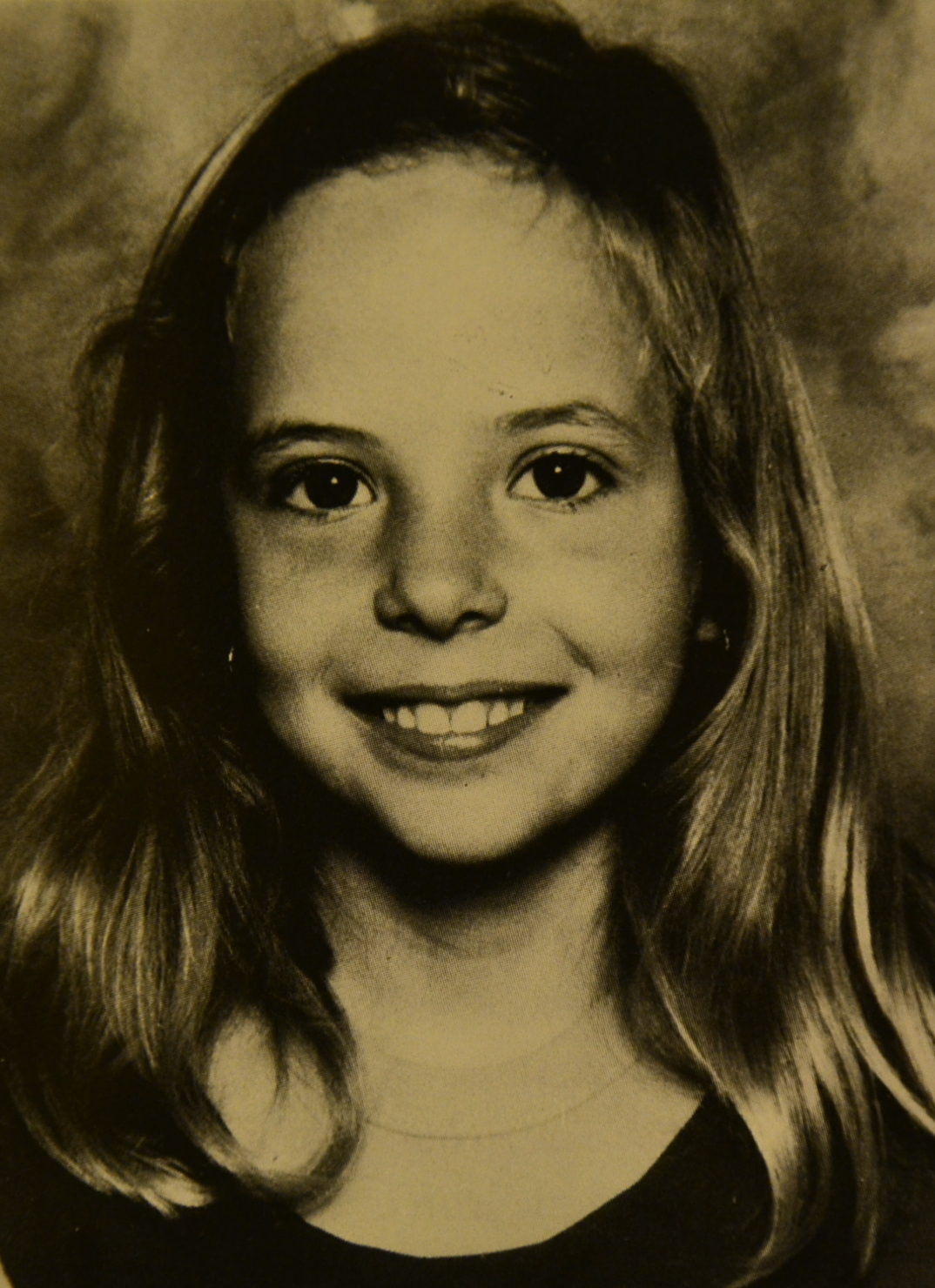

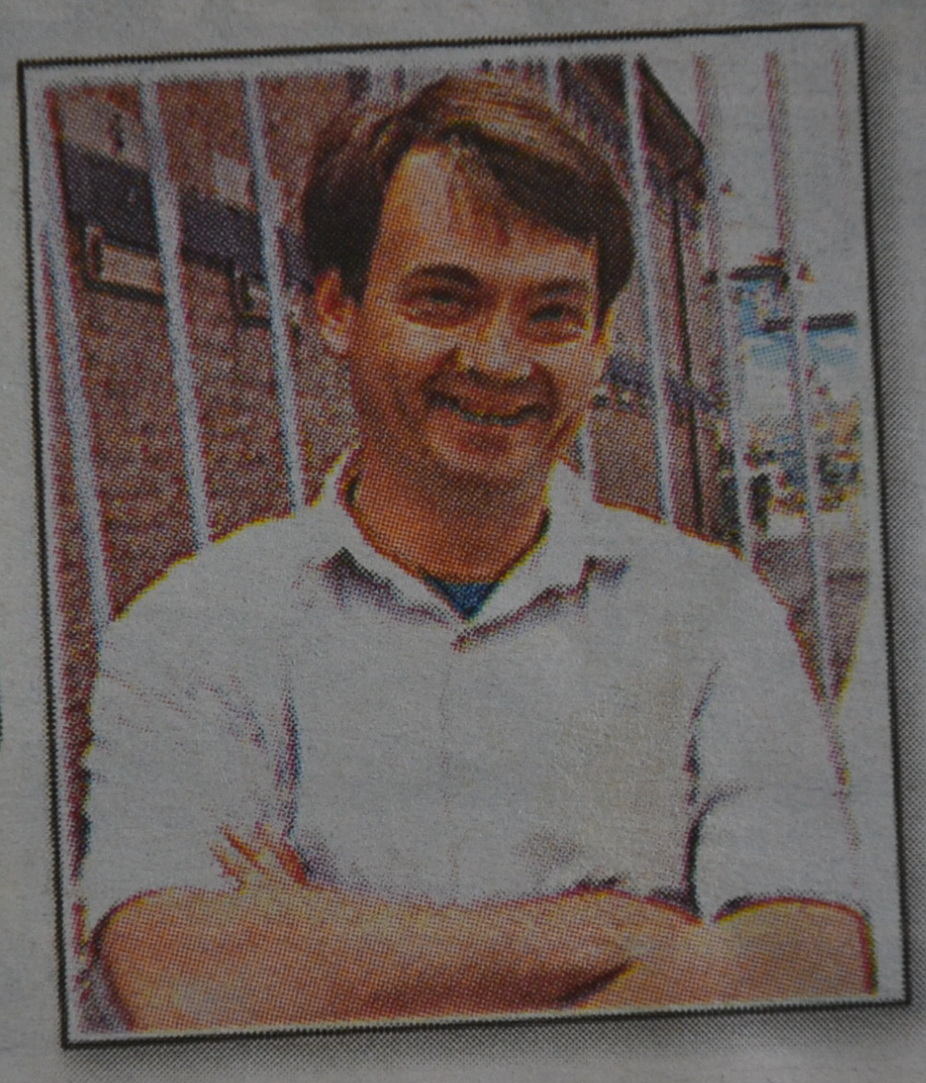

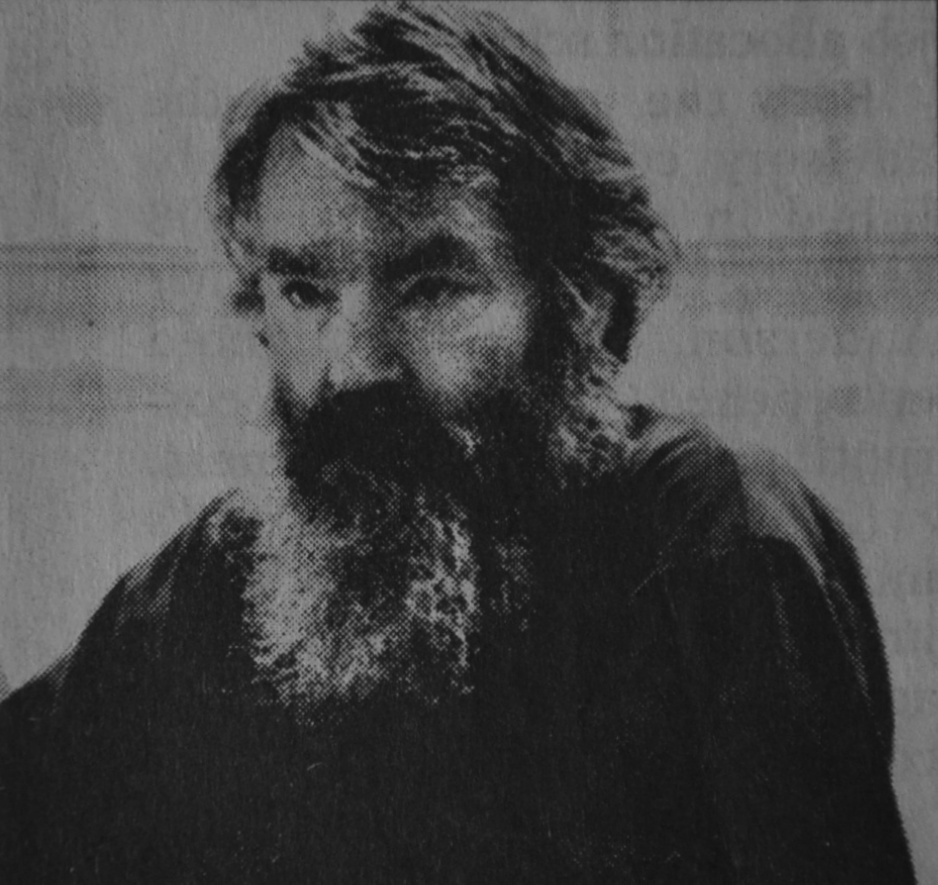

Drawing by Michael Guider, which Tim Guider believes represents the gravesite where Guider buried Samantha Above, left and right: Samantha Knight Above: (left to right): Michael Guider in 1986,

in1994, in 1996 and in 2002 Above: Samantha Knight's

parents, Tess Knight and Peter O'Meagher ARTICLE ABOUT MICHAEL

GUIDER BY NEIL PATON, AUTHOR OF

THIS SITE, WRITTEN IN 2002 I didn't know Samantha

Knight, but I knew the man who killed her. Michael Guider and I first crossed

paths at the Wayside Chapel, Kings Cross, in the late 1970s. I had worked as a

volunteer on the Crisis Centre counselling service at the Chapel, which had been

something of a passion for me throughout the 1970s. Michael Guider also worked as

a volunteer counsellor on the Crisis Centre around 1978 and I saw him at the

Wayside Chapel many times. It would be convenient and colourful to paint him as

a dark, sinister figure who looked like Dracula and always carried a bag of

lollies, but, unfortunately, the truth is much more banal. He was a friendly,

sociable person, normally known as Mick, and was capable of being quite

generous. He was also somewhat slimmer in those days, was cleanshaven and had

short hair, unlike the rather Neanderthal figure we have seen more recently in

the media. The first occasion when I met him, as far as I can remember, was when

I played a game of chess with him in the coffee shop at the Chapel. He was a

hopeless chess player, with no idea at all of how to win, and with some original

ideas of his own that were as strong as a house of cards. One occasion that stuck in my

mind was a night when I bumped into him at a coffee lounge on Darlinghurst Road,

the low-life centre of Kings Cross. A few other acquaintances gathered there

while Guider shouted everyone cappuccinos (this was in the olden days, when you

didn't have to be a millionaire to chain-drink cappuccinos). I remember Guider

saying, at one stage of the conversation, "What I love is women." This

provoked a degree of merriment, but he went on to explain that what he was

referring to was the knack that women have for making a house into a home; for

turning a dwelling into a cosy, comfortable place to live. It was clear that he

was revealing a gap in his life. (In the light of more recent events, perhaps he

should have said that what he loves is children.) In those days, there appeared

to be nothing sinister about Michael Guider. The worst thing about him seemed to

be a considerable capacity for hot air. He was a know-all whose attitude was

always that he knew more than the other person. He also had a tendency to

big-note himself. He could talk endlessly about the books he was going to write,

although he never wrote a word. I took to calling him Gunner Mick, because he

was gonna do this and gonna do that, but never did anything. I remember saying

to a friend, "He's okay, just full of air." My friend agreed, but

unfortunately neither of us knew the truth. From around 1980 I drifted

away from Kings Cross and saw no further sign of Michael Guider until I bumped

into him one day at a north shore railway station in the early 1980s. By

then I was a keen bushwalker and was on my way to a bushwalk when I saw Guider

on the station platform. It transpired that he also was a keen bushwalker, so

the conversation got onto the subject of our favourite places. We also talked

about Aboriginal sites, on which Guider was something of an expert. His capacity

for joking about himself was also on display at an early stage of the

conversation; tipping his sunglasses forward to reveal his eyes, he quipped,

"Old red-eyes is back!" This was a reference to the permanent redness

of his eyes, which he said was the result of a condition he had picked up while

working at the Cronulla sandhills some years before. The encounter ended when I

got on the train to Roseville and thence Davidson State Recreation Area (now

Garigal National Park). A few years after this

encounter, a seemingly unrelated development took place. On August 19, 1986, a

nine-year old girl named Samantha Knight disappeared from her home in the Sydney

suburb of Bondi. In no time at all, her family, aided by an army of volunteers,

had pasted up hundreds of posters all over Sydney, with the ultimate aim of

having them in every town in New South Wales. I was living at Bondi at the

time, only a few blocks from Samantha's home in Imperial Avenue. Her

disappearance triggered off an intense reaction in the local community, partly

because she was "one of ours", and partly because, with her angelic

face, she was probably a living image of childhood innocence. If you didn't know

Samantha, you soon felt as if you did. You only had to walk along Campbell

Parade, opposite Bondi Beach, and see the posters in the windows of every shop

and restaurant. "Have you seen this child?" the posters implored. No,

we haven't seen her, came the answer, but we wish we had, and we hope she will

be found. There must have been few occasions when a child had been cared about

by so many people who had never known her. The search, however, dragged on

fruitlessly, and Samantha's beautiful face slipped silently into the folklore of

Sydney. As for Michael Guider, I

crossed paths with him again later that year, only a few months after Samantha's

disappearance. Once again it was at a railway station. I was going down the

steps at Town Hall Station and Guider was coming up when we bumped into each

other. He shook my hand and congratulated me on my first guide book, which had

been published earlier that year. He told me he had bought a copy and it had

"inspired" him, meaning that he might at last put pen to paper and

produce something instead of just talking about it. I knew what he meant and

told him I called him Gunner Mick; he took no offence. In the course of the

conversation, I told him I was working on a new book about walks in the Sydney

Harbour National Park. He said he had plenty of material and I was welcome to

use it for free if I wanted to. I expressed interest and within a week or so I

was at his very humble flatette in the Sydney harbourside suburb of Kirribilli.

No sooner had I sat down than he was already giving forth the usual display of

hot air, talking as if he was going to tell me how to write the book; he, who

had never put pen to paper in his life. It turned out that he had a

great deal of material on the various parts of Sydney Harbour National Park,

especially photos and information on Aboriginal sites. His interest in this

subject was undeniably genuine and was evidenced by some of the huge reference

books he had acquired. Some of them, he assured me, were worth around $200. He

told me of rock carvings I could find and where I could find them, although his

directions proved useless when I actually went searching. (For example, he told

me there was a rock carving right by the track at Obelisk Beach, on Middle Head

in Sydney Harbour; I went there and looked, but there was no rock carving.

Another example was supposed to be a large rock carving in the middle of Mona

Vale Road, in Sydney's northern suburbs, but I went all the way along Mona Vale

Road and there was no such carving.) Another demonstration of his capacity for

hot air took place when I told him about some Aboriginal grinding grooves I had

found at Dobroyd Head, on Sydney Harbour. Without hesitation, and without the

benefit of having seen the grooves, he said, "They're not!" He went on

to explain how such grooves could be created by the wind blowing a fallen tree

-- a banksia perhaps -- back and forth, thus wearing grooves in the rock. His

explanation was absurd because the banksia would wear away long before the rock

did, but it was not meant to enlighten me. Its purpose was to establish that he

knew more about these things than I did, and this was characteristic of him. He

always took the attitude that he knew more than the person he was talking to; a

sure sign of low self-esteem. While we were talking, he

eventually held up some material of a very different kind: a newspaper clipping

about Samantha Knight. Brandishing the page from an old tabloid, he told me that

he knew Samantha. As he talked, he betrayed not the slightest trace of feeling,

and this was only a few months after he had killed her (if I can get ahead of

myself for a moment). At the time, though, there was no reason to think there

was any connection between him and Samantha's disappearance. I kept various notes and

photos that Guider said I could use, although he understandably declined to let

me borrow his valuable books. Some of his material appeared in the new guide

book when it was published in 1987. At the front of the book I placed an

acknowledgement in which I thanked him for letting me use his material; I also

sent him a complimentary copy. I never saw Guider again, and

years were to pass before anything would happen to remind me of him. In the

meantime, there was one occasion when I saw Samantha's mother, Tess Knight,

working in a city bookshop on a Sunday afternoon in 1992. I recognised her from

pictures in the papers, not to mention the name-tag she was wearing, but we did

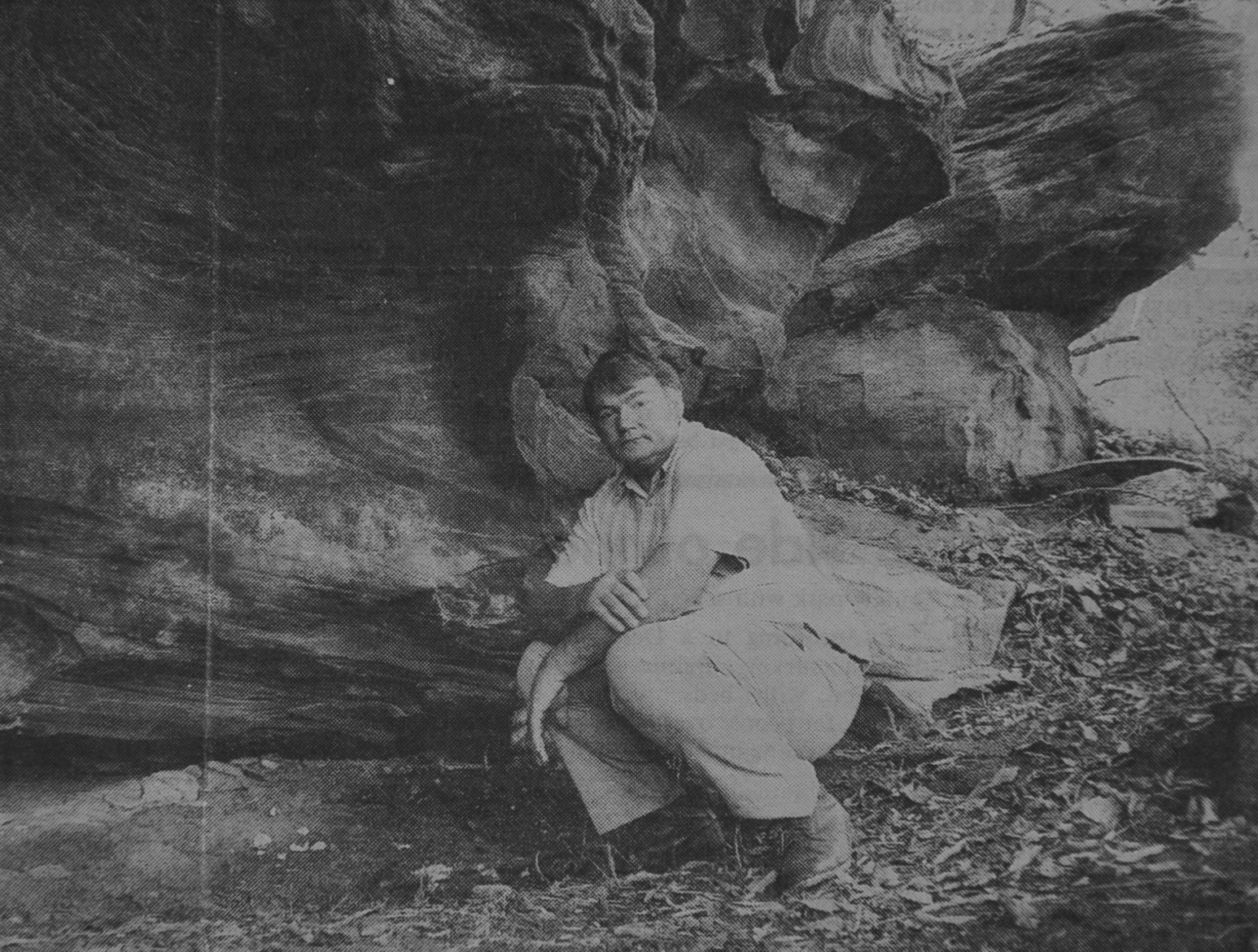

not speak. That was the first and last time I saw her. In July, 1994, I saw a local

paper called The Glebe, in which there was an article about the renaming

of Long Nose Point in the suburb of Birchgrove. Leichhardt Council had just

taken the step of returning the point to its old Aboriginal name, Yurulbin. The

article explained that "amateur archeologist" Michael Guider had

played a role in the campaign to have the point renamed. It was true that Guider

had had some respect as something of an expert on Aboriginal culture and sites

around Sydney, and the article was illustrated with a photo of him in a rock

shelter at the point. Someone passed the clipping on to me because they thought

I would be interested in the subject matter, unaware that I knew Guider. At the

time, I put the clipping on file and promptly forgot about it; I was surprised

recently when I went through my files to see if I had anything on Samantha

Knight, and saw the photo of Guider at the point. A couple of years later, in

1996, a bombshell was to drop in the form of two newspaper articles published on

September 29 and October 1. The first article said that police were exploring a

possible link between Samantha Knight and a middle-aged man who had apparently

known her. The next article said the man in question was one Michael Guider, who

had just been sentenced to a minimum of ten years imprisonment for sixty

offences of pedophilia. The article of October 1 had a photo of Guider with a

camera in his hands, which confirmed to me that the man in question was indeed

the Michael Guider I had known from the Wayside Chapel. It was an enormous shock;

most of us would find it hard to believe that someone we know is involved in

such activities, and I was certainly no exception. I showed the article to Bill

Crews, who used to run the Crisis Centre when Guider was there. It turned out

that he had already seen it, and he told me how shocked he had been. No doubt

there had been a number of similarly shocked people all over Sydney. I remember

telling a friend about it and saying, "I knew he was a bit screwy, but not

that screwy." I heard no more of

Guider until a lengthy article by Philip Cornford appeared in the Sydney Morning

Herald on August 8, 1999. Once again, a possible link between Guider and

Samantha was explored, in addition to which the article went into Guider's life

story in great detail. It was obvious that he had come from a grossly

dysfunctional family -- what there was of it -- and had himself been sexually

abused at various stages of his life. He had apparently lived in an intense

fantasy world and, according to one psychologist, showed no remorse over his

pedophile activities; a fact that was mirrored in his lack of feeling when he

talked to me about Samantha, only months after he had killed her. He had a

tendency to blame other people, especially the mothers of the children, for his

deeds. According to some professionals, starting with M. Scott Peck, author of The

Road Less Travelled, this tendency to blame everyone else for one's failings

is a characteristic of personality disorders, of which Guider no doubt has more

than his fair share. By this time, more evidence

was apparently emerging, leading to more coverage in the media in 2001.

Prisoners who had known Guider in gaol told of conversations in which he said he

had accidentally killed a girl. He had, he said, doped her with a sleeping

tablet, with the intention of molesting and photographing her, but had

accidentally given her an overdose. They would never find her, he allegedly told

his fellow inmates. I vividly remember reading

these articles while having a cup of coffee in Randwick shopping centre. It was

clear by now that Guider had been responsible for Samantha's death. I had never

known Samantha, but I can say, without being melodramatic, that as I read these

articles I felt like killing Michael Guider. It was the only time in my life

when I felt like killing someone. It is bad enough when anyone does things like

this; when it is someone you know, it seems a thousand times worse. I later described all this to

a friend who has a law degree, including the occasion when Guider had betrayed

no feeling at all as he told me he knew Samantha. My friend wondered if I might

go to the police with what I knew about Guider. I considered it, but the reality

was that I had no information about Guider that proved anything, except that he

apparently had no feelings. It soon turned out, in any case, that no evidence

was needed, because Guider eventually pleaded guilty to manslaughter. Things moved along in the

next year, and at the time of writing there has been a preliminary hearing in

which the court determined there was sufficient evidence to justify sending

Guider to trial, and in which Guider maintained his innocence; and the more

recent court appearance in which Guider pleaded guilty to the manslaughter of

Samantha. This plea was, the papers tell us, the result of intense negotiation

between Guider, the prosecution and lawyers. The offence of manslaughter carries

a maximum penalty of twenty-five years imprisonment. Now we wait with baited

breath to see what sentence the court will hand down. Even if Guider gets the

maximum penalty, it will not bring Samantha back and it will not erase the pain

her parents have been through, but at least they finally know what happened to

their daughter. What remains to be seen is whether Guider can give up his old

activities when he is finally released. The idea of protecting the community

seems to have been largely abandoned by our society, even when the community

consists of innocent children. (Copyright N.Paton 2002) FURTHER READING FOREVER NINE, Hofman

and Kidman (Five Mile Press) 2013 GOOD BROTHER BAD BROTHER, Tim Guider, 2020