THE CRIME OF

THE PAPIN SISTERS

In February, 1933, the whole of France was horrified to learn of an unspeakably savage double murder that had taken place in the town of Le Mans. Two respectable, middle-class women, mother and daughter, had been murdered by their maids, two sisters who lived in the house. The maids had not simply killed the women, but had gouged their eyes out with their fingers while they were alive and had then used a hammer and knife to reduce both women to a bloody pulp. In both cases, there were no wounds to the body. Apart from some gashes to the daughter's legs, the full force of the attack was directed at the heads and the victims were left literally unrecognisable.

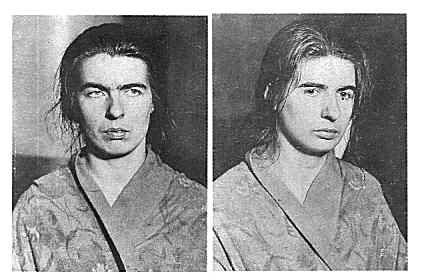

Top, the Papin sisters in a studio portrait,

circa 1927 (Lea is on the left, Christine on the right)

Adding the bizarre to the

horrifying, the maids made no attempt to escape and were found together in bed,

naked and in each other's arms. This naturally added a dimension of scandal and

titillation to the case. Were the maids having a sexual relationship? If so, it

was both homosexual and incestuous. Overnight, the two sisters, aged 21 and 27,

became infamous. The public was inflamed in a way that rarely happens unless a

particularly brutal and large-scale massacre takes place. The tabloids went

berserk, calling the sisters colourful names

like the Monsters of Le Mans, the Lambs Who Became Wolves and the Raging Sheep.

Suddenly the names of Christine and Lea (pronounced Lay-ah) Papin were known

throughout the land. Almost as striking as the horrifying murders was the

contrast between the violence and the reserved demeanour of the sisters. They

had worked for their employers for seven years and had always been quiet,

hard-working and well behaved. Their work references described them as honest,

industrious and proper. Needless to say, they had no criminal record. They had

always spent their spare time together, appeared to have no vices and were

regular church-goers. Yet suddenly, and without the slightest warning, these two

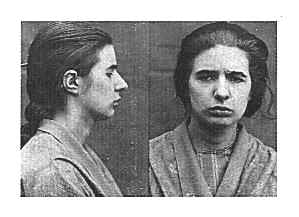

quiet maids had turned into monsters. The Papin sisters photographed after their

arrest. While most of the French

population simply wanted to lynch the sisters, others were intrigued and wanted

to understand what had happened. The latter had plenty of grist for their

intellectual mill. Theories abounded, focusing mainly on the idea that the

murders had been an example of class warfare. The psychoanalysts also weighed

in, finding fertile material in the eye-gouging and the apparent sexual

relationship between the sisters. Almost eight months elapsed between the

murders and the trial, providing ample time for fevered imaginations to dream up

theories. Even while in prison awaiting their trial, the sisters managed to

provide more food for thought. The elder sister, Christine, spent much of her

time crying out for Lea and begging to be reunited with her. She rolled around

on the floor in apparent paroxysms of sexual agony and sometimes expressed

herself in sexually explicit language. When not crying for Lea, she experienced

apparent hallucinations and visions. During one such attack, in July 1933, she

attempted to gouge her own eyes out and had to be put in a straightjacket. Lea Papin after her arrest. On the day after this attack,

Christine called for the investigating magistrate and gave him a new statement

in which she said that she had not told him the whole truth before; that she had

killed the two women, Madame and Madamoiselle Lancelin, on her own as a result

of a kind of "fit" coming over her; and that Lea had not taken part in

the murders. The investigating judge dismissed this statement as merely a

spurious way of trying to set Lea free, and the jury at the trial treated it

with equal contempt. Moreover, Lea persisted in saying that she had taken part

in the murders. The trial, in September, 1933,

was a national event, attended by vast numbers of public and press. Police had

to be called in to control the crowds outside the packed courthouse. There were

moments during the trial when the judge had to threaten to clear the court in

order to control the emotional reactions of the people in the public gallery,

particularly when the eye-gouging was described. Naturally enough, the girls

denied having had a sexual relationship, but never made any attempt to deny the

murders. Not surprisingly, they were found

guilty of murder and Christine was sentenced to death on the guillotine. As the

sentence was pronounced, she fell to her knees and had to be assisted by her

solicitor. Lea, for her part, was found guilty of the murder of Madame Lancelin

but had not been charged with the murder of the daughter, Genevieve, because

doctors concluded that Genevieve had died before Lea had joined in the murders.

The younger sister was sentenced to ten years' hard labour.The jury had found

some extenuating circumstances in her case because she had been completely

dominated by the overweening Christine. Christine's sentence was later

commuted to life imprisonment, the normal procedure in the the case of women.

However, her condition deteriorated rapidly in prison. Profoundly depressed over

being separated from her beloved Lea, she refused to eat and became

progressively worse. Transferred to the asylum in the town of Rennes, she never

showed the slightest sign of improving as time went by and died in 1937. The

official cause of death was "cachexie", ie wasting away. The Papin sisters during their trial in

September, 1933, looking as though they have aged twenty years. In front of them

are their attorneys. Lea, on the other hand, continued

to be her usual quiet, mild-mannered self while in prison and was released after

eight years, gaining remissions for good behaviour. She was then joined by her

mother, Clemence, and they settled in the town of Nantes, south of Rennes. Lea

worked as a hotel chambermaid, going under the false name of Marie. In 1966 the

French writer Paulette Houdyer produced a book, L'Affaire Papin, which

told the story of the Papin sisters in an unfortunately novelish format.

Apparently as a result of this book, Lea was interviewed by a journalist from France-Soir.

In this interview we learn that she experienced vivid visions of Christine

appearing before her in spirit form and was certain that her sister was in

paradise. She still kept old photos of Christine, as well as an old trunk

crammed with beautiful dresses that the girls had made for themselves before the

murders. She also stated that she was saving to return to Le Mans and rejoin her

other sister, Emilia, who had become a nun at the age of sixteen, but there is

no evidence that she did so. The interview in France-Soir is the last

record of the lives of the Papin sisters.It was thought for many years

that Lea had died in 1982 at the age of seventy, but the French film-maker

Claude Ventura recently repudiated this idea. In the course of making his

documentary film, En Quete des Soeurs Papin, Ventura found various

inconsistencies and anomalies in the official records. As a result, he made the

astonishing discovery that Lea had not died in 1982, as everyone had thought,

but was still alive at the time he was making his film. Although not widely known outside

France, the Papin sisters have, as the years have gone by, had an impact that

few people, criminal or otherwise, have had. At the time of writing, there have

been something like three plays, three films and a number of books based on

these benighted girls, plus numerous articles. Even most celebrities, French or

otherwise, cannot boast of a record like that. The Papin sisters have a

remarkable capacity for intriguing people, fascinating them and provoking them

to intellectual and creative efforts. Probably only Jack the Ripper has provoked

a greater outpouring. The Papin case is a psychological

one as much as a criminal one, and it has already been noted that the

psychoanalysts had a field day with the sisters. Looking at them from a modern

perspective, however, it is clear that Christine Papin would nowadays be

diagnosed as a paranoid schizophrenic. In the 1930s there was no effective

treatment for her malady, but these days she would be treated with major

tranquilisers and would probably have a longer life, if not a happy one. Her

sister Lea, on the other hand, never showed signs of being psychotic and there

is no reason to believe that she was. She appears to have been very timid,

anxious and prone to panic states when under stress, and probably suffered from

anxiety disorders. She also had rather low intelligence and was dominated by her

older sister. During the trial, doctors testified that Lea's personality seemed

to have disappeared completely into Christine's personality. Lea was, by all

accounts, a shy, good-natured and gentle person. Employers never had a bad word

to say about her, whereas Christine had a "difficult" personality and

had sometimes been dismissed for insolence. Lea's tragedy was that she was so

dominated by Christine. If she had been separated from Christine at an earlier

stage, she certainly would have led a blameless life and never would have passed

through a prison gate. One perceptive employer had, in fact, suggested to Lea's

mother that she should place the girls in separate jobs because Christine was a

bad influence on Lea but, unfortunately for Lea, the suggestion was ignored. That the sisters had severe

problems is not surprising in view of the family history. Their paternal

grandfather had been given to violent attacks of temper and epileptic fits. Some

relatives had died in asylums or committed suicide. Their father, Gustave Papin,

had had a drinking problem and had also raped their sister Emilia when she was

nine years old. This attack had precipitated their parents' divorce, after which

Christine and Emilia had lived in an orphanage at Le Mans for several years. Lea

had been looked after by an uncle until he had died, then she too had been

placed in an orphanage until she was old enough to work. Their mother had

visited them regularly during this time but there was always a certain degree of

friction between her and Christine. Approximately two years before the murders,

there was a complete rift between the girls and their mother, apparently caused

by disagreements over money. Their mother wrote to them on occasion after this

rift, but was ignored. The one constant in the lives of

the sisters, and their only enduring emotional tie, was their devotion to each

other. They worked together whenever they could and it was thus that they ended

up in the Lancelin household in 1926. Christine started working there first and

within a few months had persuaded the Lancelins to take on Lea as well.

Christine worked as the cook and Lea as the chambermaid. It seems that their

contact with the family was minimal and their employers rarely bothered to talk

to them. They shared a room on the top floor of the Lancelins' three-storey

terrace and kept largely to themselves. They went to Mass every Sunday,

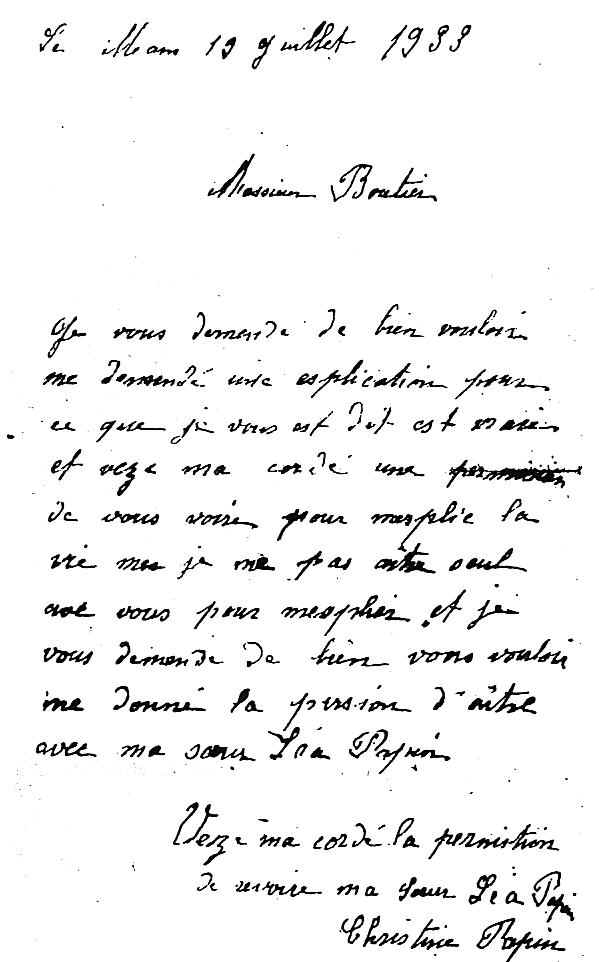

but appeared to have no interests apart from each other. A letter written by Christine Papin when she

was in prison, begging to be reunited with her sister Lea. Psychologically, the girls in

fact became enmeshed in a condition known to the French as folie a deux:

literally, madness in pairs, otherwise known as shared paranoid disorder.

Characteristically, this condition occurs in small groups or pairs who become

isolated from the world at large and lead an intense, inward-looking existence

with a paranoid view of the outside world. Most couples who commit murders

together in fact have this kind of insular, inward-looking relationship. It is

also typical of shared paranoid disorder that one partner dominates the other,

and the Papin sisters were the perfect example. According to statements made by

some witnesses, Christine became increasingly agitated and manic in the months

leading up to the murders. Her condition was obviously worsening, and on the

evening of February 2nd, 1933, her madness finally came to a head. She attacked

first the mother and then the daughter, gouging with her fingers. At some stage

she was joined by Lea and the attack was continued with a hammer and knife, plus

a pewter pot that stood in the hallway. It seems to have lasted for

approximately thirty minutes, after which the victims were literally beyond

recognition. The sisters then washed the blood from themselves, went to their

room, disrobed, climbed into bed and waited for the police to arrive. They made

no attempt to escape and no attempt to disguise their deeds. As has already been noted, the

Papin sisters have had a remarkable impact, giving rise to a string of works

about them or otherwise related to them. The first was the play The Maids,

by Jean Genet, which was first produced in 1947, while Lea was still alive and

probably when she was working in the hotel. Genet's play was followed eventually

by other plays and films, plus a never-ending stream of articles and books. It

is a remarkable record for two benighted maids whose lives would have remained

dark and obscure if not for two hideous murders committed on a winter's night in

Le Mans. NEWS By the year 2000, it was claimed that Lea Papin

was still alive in a hospice somewhere in France. This

discovery was made by the film-maker Claud Ventura while researching

his film "En Quete Des Soeurs Papin" (In Search of the Papin Sisters).

The Lea Papin in the film died on 24th July, 2001, and was buried next to the Papin sisters' mother, Clemence, who died on 10th January, 1957.They are buried in the Ciemetiere de la Bouteillerie, in Nantes, where Lea lived after getting out of prison. See the link "NEW PIX OF THE PAPIN SISTERS" on the Home page for photos.