Through the service door an

aging maid going grey, wearing a grey blouse and grey dress, leaves

every Saturday at 5pm precisely, the luxury hotel where she has worked

all week. She walks through the grey streets of an old town in the west

of France, but I have sworn to keep the name secret.

She carries at her side a grey shopping bag bulging

with the white aprons rolled around an identity card that she has not

shown to anyone for more than twenty years. On that document, grey from

wear, is printed her true name: Lea Papin, born Le Mans, 1912. Since

leaving prison in 1941, she has tried to escape the curse of that name,

which her employers do not know about. In vain!

She can reflect with delight, kneeling in the chapel

of the Virgin, where she never fails to stop when she is going home for

the weekly break, that the Virgin is named Mary, Lea's adopted alias.

Her prayer is poisoned by her deception. She gains relief, making on the

shopping bag a furtive sign of the cross, and going back across the

street towards her room. She locks the door and stretches out on her

iron bed.

And there she is, that famous Marie, full of her past.

And this is Lea, the rebel, the lover and the criminal who rises from

the core of her flesh and her memory.

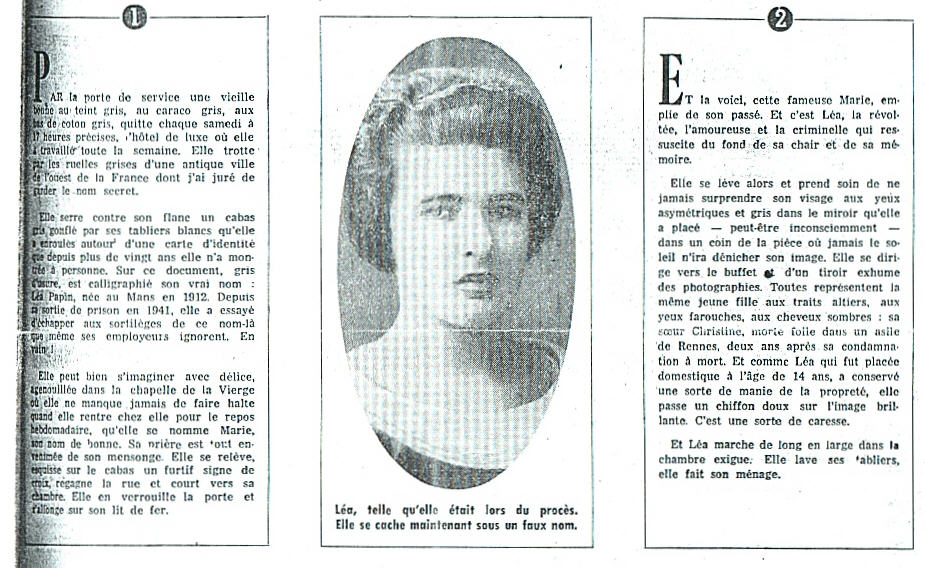

She gets up then and takes care to never surprise

herself by turning her grey and asymmetrical eyes to the mirror that is

placed -- perhaps unconsciously -- in a corner of the room where the sun

can never flush her out. She heads towards a wardrobe and takes some

photographs from a drawer. They all depict the same young woman with

haughty features, fierce of eyes and dark of hair: her sister Christine,

who died while mad in the asylum at Rennes, two years after being

condemned to death. And as Lea, who has worked as a domestic since the

age of fourteen, has retained a kind of mania for neatness, she passes a

soft cloth over the shiny image. A kind of caress.

And Lea walks back and forth in the cramped room. She

washes the aprons, she makes her dinner.

She confesses:

"I do what I can to keep my room simple so that

my sister, who watches me from above (because I'm certain she is in

Paradise), doesn't laugh at me. I pray for her. I pray for our mother

who lived with me until she died. To help me, she said...and all

at once I didn't pray anymore. Christine watches me. She is always

beautiful and young. She smiles as in the old days: with irony! I come

apart, I shrivel up, I sweat from fear, I faint...And there's a trunk in

my room."

|

It is a trunk with an old

lock, with a round lid that comes up creakily and which is fastened by

two little bolts that lock. Quite a ceremony is needed to find the keys,

to force them, turn them, tear them back, open the strips of metal which

hang on hooks on the side of the chest.

"I've got it," says Lea, feeling like a hand

that paralyses my wrists, and I throw the keys...It seems to me that I

have committed an evil action. I am shaking. I am getting old.

It is a fact that the chest is brimful of sin. It

overflows with lacy collars, linen, of woven fabrics styled in the

manner of other times. They are the costumes that the Papin sisters, the

maids, made for special occasions, in their garret, while Madame was

content with ordinary linen.

Christine of the fierce eyes made hems as wide as two

fingers. Lea, younger and more stylish, wrapped herself in the white

vapours of Alencon lace. Lacy collars and fabrics, despite Lea's

neatness, are going as grey as her hair and like her shadow which,

having dressed up these relics, displays them in the room to the blinded

mirror...

Intoxicated from incantations, on Monday, Marie the

maid -- pardon, Lea! -- resumes her work at the luxury hotel.

They often give her the silverware to prepare. The

knives are not ready. If something gets damaged, her blood freezes. One

is not surprised by the memories of these gestures; she washes her

hands, brushes and pumices them much longer than the younger girls, her

workmates, who give her a friendly slap on the back:

"So Marie, are you dreaming?"

The grey Marie with the red hands, ie Lea with the

bloody hands, tilts her head under the stream of water. She needs that

purification, which she must renew until her death, if she never wants

to feel the sting, like a needle, at the slightest trace of blood...

Haunted by the past, which burns to the point of

reducing her to the colour of ashes, Lea Papin pursues her gentle

madness until her testament:

"When I don't have to work anymore, I want to

become Sister Marie, at Bon Pasteur, in Le Mans. I've been saving for

it. At Bon Pasteur, one of my older sisters is a nun. I'll go back to

her..."

........George Sinclair

(Translated from the French by Neil Paton. Translation Copyright N. Paton 2001)

BELOW: ORIGINAL ARTICLE IN FRENCH.

BACK TO CHRISTINE AND LEA

PAPIN